Consumers are battening down the hatches and recession in developed economies appears to be on the way, if not here already.

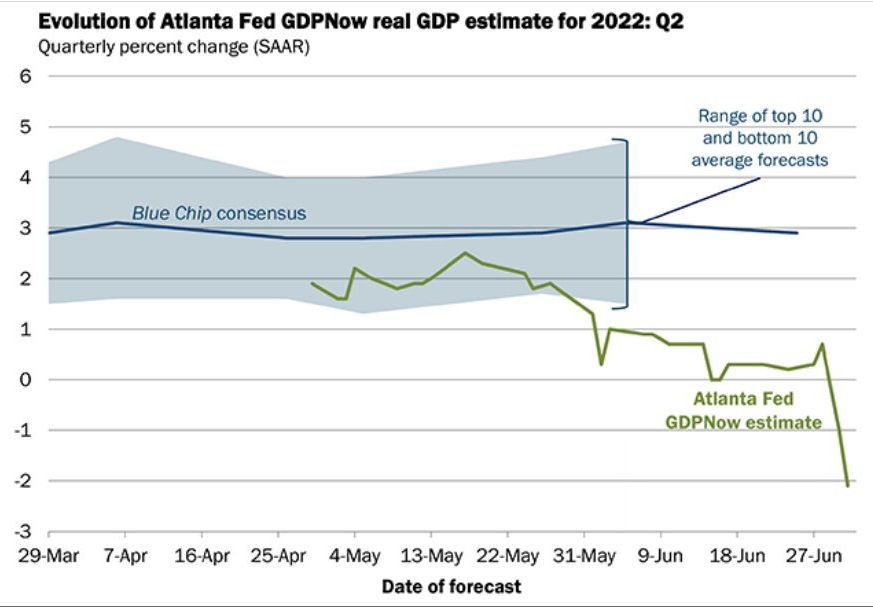

Economists have been busy with their red pens, downgrading their GDP forecasts at an alarming rate; the widely watched Atlanta Fed GDPNow reading for US growth fell to -2.1% for Q2 on July 1, a rapid reversal from the +1.9% it showed at the end of May. A second consecutive quarter of negative growth thus looks nailed on and, according to analysts at Nomura, could drag on for over a year. And when America sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold. Indeed, UK GDP fell by 0.3% in April 2022 - it's hard to see where any immediate recovery could come from.

Those recessionary impacts are now starting to show up clearly on the RNS. "Our customers are watching every penny and every pound” said Sainsbury’s chief executive Simon Roberts in a trading statement this week. “The pressure on household budgets will only intensify over the remainder of the year”. Its like-for-like retail sales, ex-fuel, slipped 4.5% in the first quarter, led by a horrible performance in general merchandising where sales are now 6.2% below pre-pandemic levels.

Sainsbury’s statement reflects much of what we’re already seeing in wider consumer surveys, and other areas of the economy like the all-important housebuilding sector, where activity fell for the first time in two years in June. Today brought yet more data documenting the depths of despair many are feeling, this time from Which?, whose consumer confidence index in the future UK economy plunged to -70, the lowest reading since the pandemic struck.

Recent confidence surveys in the US and Eurozone paint much the same picture. German consumer confidence, for example, plunged to a record low in June after a brief respite in May, which at –27.4 hit the lowest level since records began in 1991.

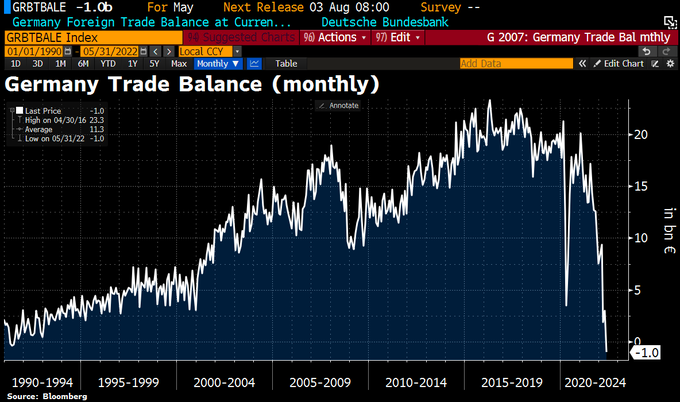

Perhaps more worrying still is the German trade balance, which fell to a negative reading for the first time since 1991. That’s hardly surprising – judging by the latest data from the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders, new BMW’s aren’t exactly flying out of the showrooms; just 141,000 new cars were registered in June, the lowest level since 1996 and a fall of 24.3%.

The culprit is, rather obviously, inflation, with soaring prices of energy and food seeing consumers and businesses around the world tightening their belts. Google searches for recession have rocketed, important as even talk of an imminent recession is enough to trigger one – if people think there’s more financial pain ahead they’ll moderate their behaviour. The retreating oil price is indicative that traders are also preparing for the prospect of a long period of weaker growth.

Equity markets, however, seem to be welcome the prospect of a recession as an alternative to inflation, not as strange as it may seem on the basis that a recession may discourage the Fed from tightening too much and cutting off the monetary support the market has become addicted to. Bonds, which had sold off sharply in anticipation of a period of severe monetary tightening, are rising again as investors search for safety and bet on less aggressive rate increases.

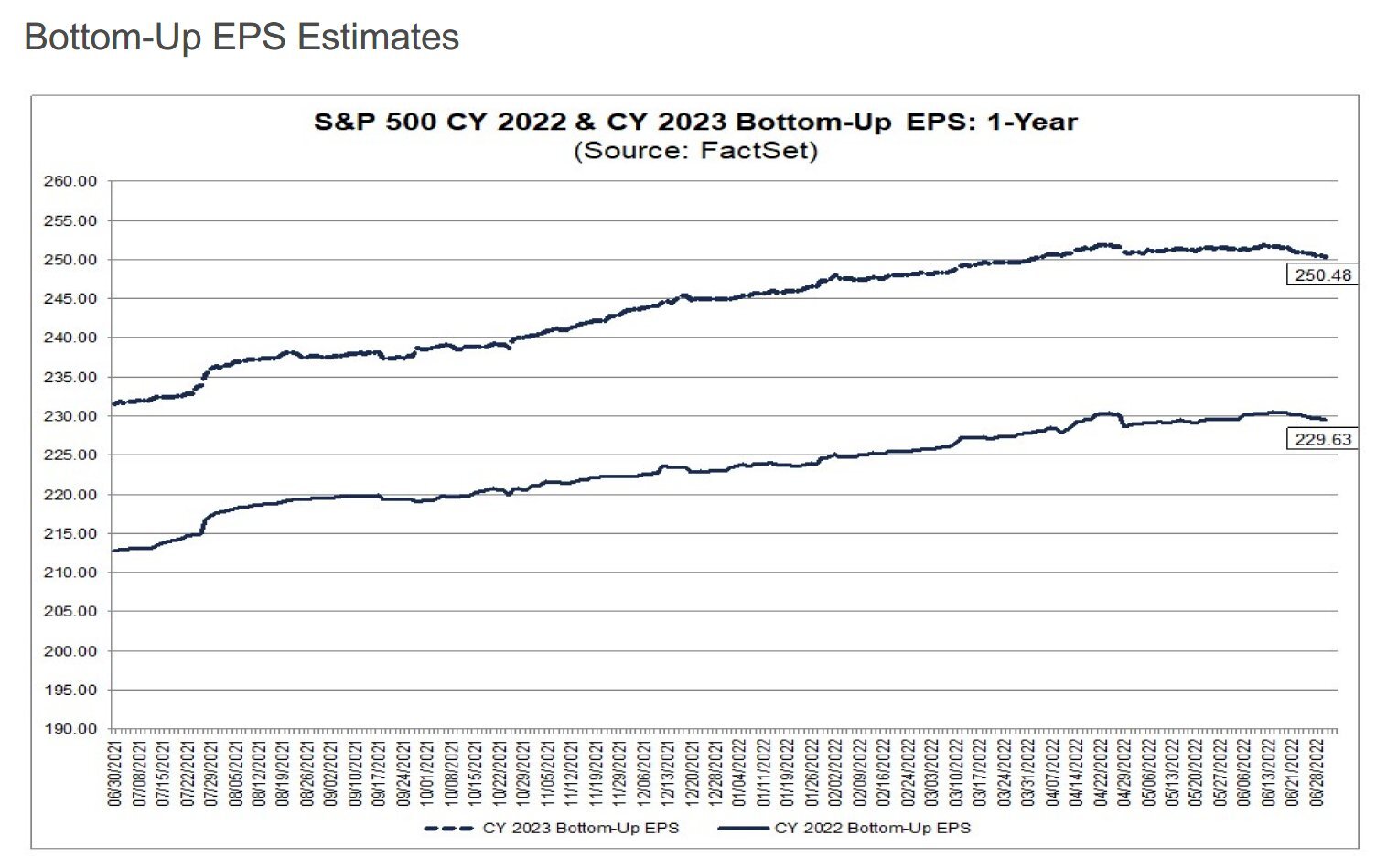

But, as Vox analyst Paul Hill noted to me this week, the flipside is that corporate earnings expectations may still be too high, even if inflationary pressures like high energy prices are receding. As he points out, S&P corporate earnings are currently expected to climb 8.6% in 2023, but forecasts will almost certainly have to be reset lower after the forthcoming Q2 22 earning season as it starts to show the impact of the brewing slowdown. He thinks the markets are - based on the current 2023 PE of 16 - already pricing in a 4%-5% drop in FY23 EPS growth expectations to $239/share, but reckons there could be more market volatility ahead as overleveraged traders are forced out of the market.

I agree, but wonder if the downward earnings revision could be deeper still, especially as it's quite possible that residual inflationary effects will stick around for some time and continue to dampen economic activity. “The risks are firmly on the side of inflation becoming more ingrained in the system”, said former Bank of England governor Mervyn King in a recent interview, reflecting broader concerns that even if commodity inflation moderates wage inflation, driven by a tight labour market, might accelerate. “When you get an intellectual mistake in policy, and you allow inflation to start to rise, if you’re then hit by bad luck - which is what happened in the 1970s and has happened now it – it becomes something of a very unpleasant outcome and it takes tough action.”

In other words, central bankers won’t be able to hold back rate rises as they continue to tackle inflation, as many in the market hope. And if a slowdown also becomes entrenched - as seems likely - that will only mean one thing: stagflation, and more economic and market pain ahead.