Results from Lloyds Banking yesterday rounded up the reporting season for the UK banks. And while the results have been largely good, the market’s reaction has been anything but positive, with shares down heavily across the sector. Lloyds (LLOY) shares initially slipped 2%, and have now fallen 5% since peaking in mid-February. NatWest (NWG), Barclays (BARC) and HSBA (HSBA) have performed similarly, bringing to an abrupt end a strong rally over the last four months.

The weakness reflects nervousness in the outlook rather than disappointment with recent trading performance. In particular, investors finally appear to have woken up to the double-edged sword that rising interest rates present to the sector.

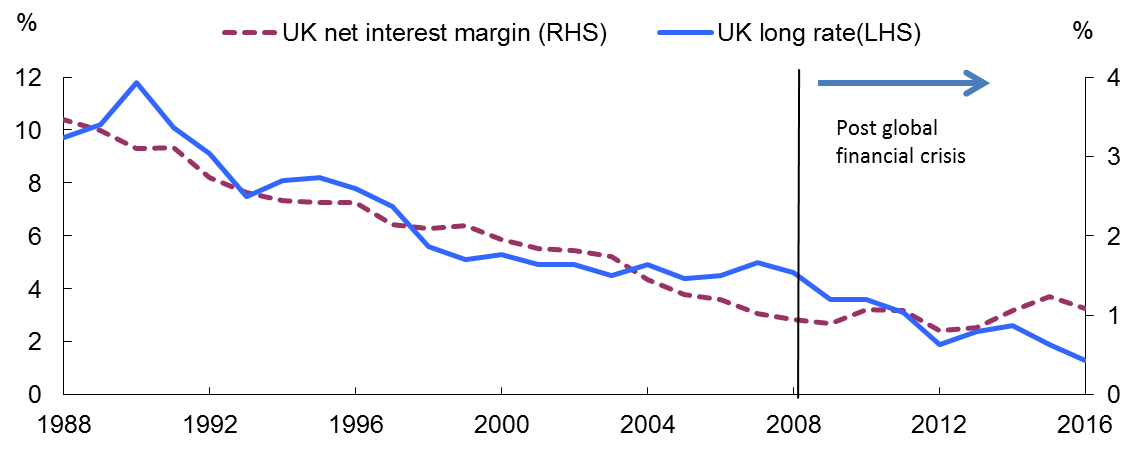

The return of higher interest rates is, on the face of it, good news for the UK banking industry. Banks make a large chunk of their money by being able to borrow money at a cheaper rates than the ones at which they lend. That difference is called the net interest margin, and in times of low interest rates – the conditions we’ve had for years – this metric tends to contract, as this chart shows.

The effect of higher rates can be clearly seen in the results from the banking sector so far this year. Lloyds saw its net interest margin rise from 2.54% to 2.94% over the year, hitting 3.22% in the fourth quarter and driving net interest income 49% higher to nearly £14bn.

Meanwhile, NatWest’s operating profit jumped by a third in 2022, to £5.1bn, again helped along by a better net interest margin on its loan book, up from 2.3% in 2021 to 2.85%, and hitting 3.2% in the final quarter. That lifted net interest income by almost a third to £9.9bn, including a 51.4% jump in the fourth quarter.

And Barclays – whose overall figures were hit by a trading error in the US and a dealmaking slump that saw fees in its investment banking division – added £0.8bn to UK income as its net interest margin climbed 34 basis points to 2.86%.

The double-edged sword, of course, is the problem that while higher interest rates are good news for the banks, they’re not such good news for their customers, which as well as growing used to many years of low rates are now feeling the pinch from higher borrowing costs to compound the inflationary pain they’re already feeling.

As a result, banks are under increasing pressure to increase savings rates for customers, especially as they increase dividends, buybacks and their own pay. And however unwilling the banks may be, competition for deposits may do the job for them anyway. NatWest guided to a 2023 net interest margin of 3.2% in 2023, flat on the final quarter and 18 basis points below analysts’ expectations

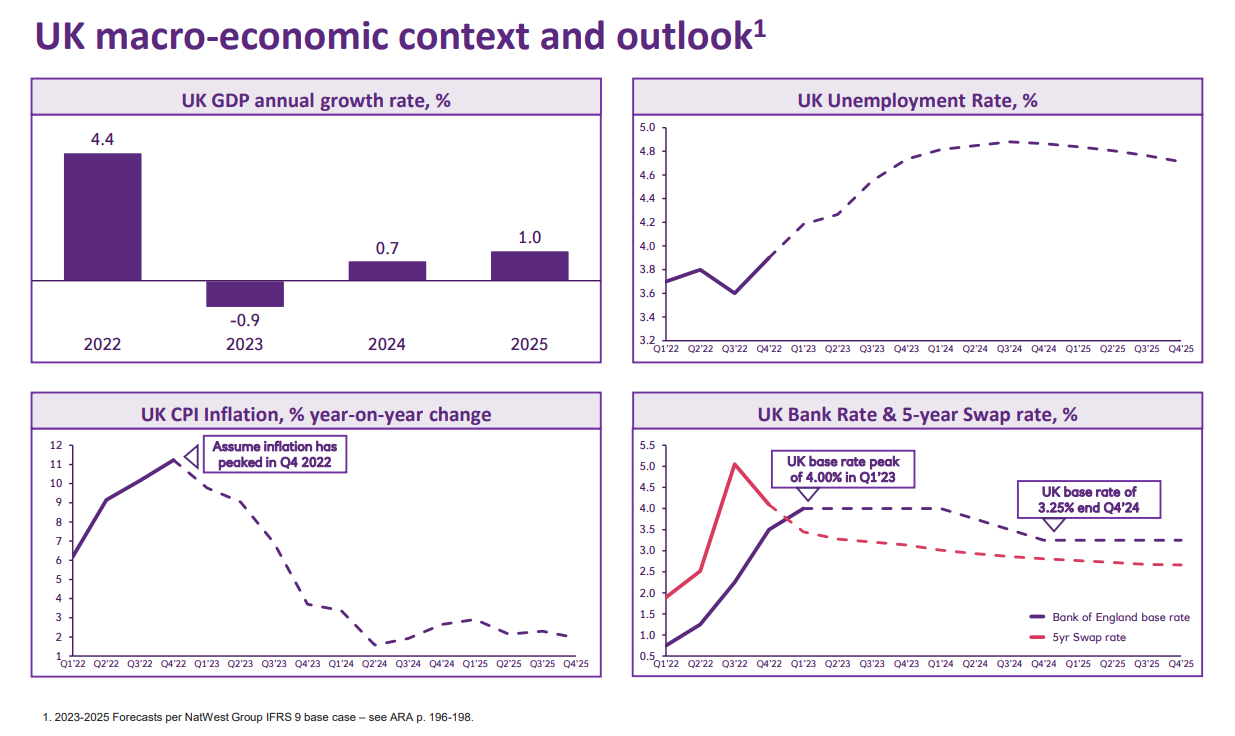

They’re also having to raise impairments to account for the potential worsening of the UK economy, as NatWest usefully demonstrated in its own results presentation (chart below). Lloyds recognised impairment charges for potential bad debts of £1.5bn, a far cry from the £1.3bn of provisions it released last year. Barclays reported provisions of £1.2bn, a similar level to NatWest.

That’s not to say that the UK’s banks won't cope with any downturn should it come, having got themselves back in since the financial crisis by trimming costs and strengthening their balance sheets. A key measure of that is higher tier-one capital ratios across the sector, an indicator of banks’ financial stability. All now hover around the 14% mark, a far cry from the reckless 4% seen when the financial crisis struck.

And it’s quite possible that the gloomy tone from the UK’s lenders should instead by interpreted as ‘sensibly cautious’, given the plethora of economic moving parts behind their business.

Nevertheless, after a good run after the volatility brought about by the catastrophic Truss-Kwarteng mini-budget in September, it’s also sensible to expect that near-term progress in the sector is likley to be slower, even if the potential headwinds it faces can now be measured as a stiff breeze rather than a strong gale.

The housing market, in particular, is cause for genuine nervousness, if prices keep falling and buyer confidence dries up further. That worry may ease if inflation and interest rates fall, but then the banking sector’s ability to generate profit growth will be constrained too. So while their shares hardly look expensive, especially on the basis of forecast dividend yields ranging from 3.9% (HSBC) to 6.7% (Natwest), that’s a fair reflection of a more difficult outlook.